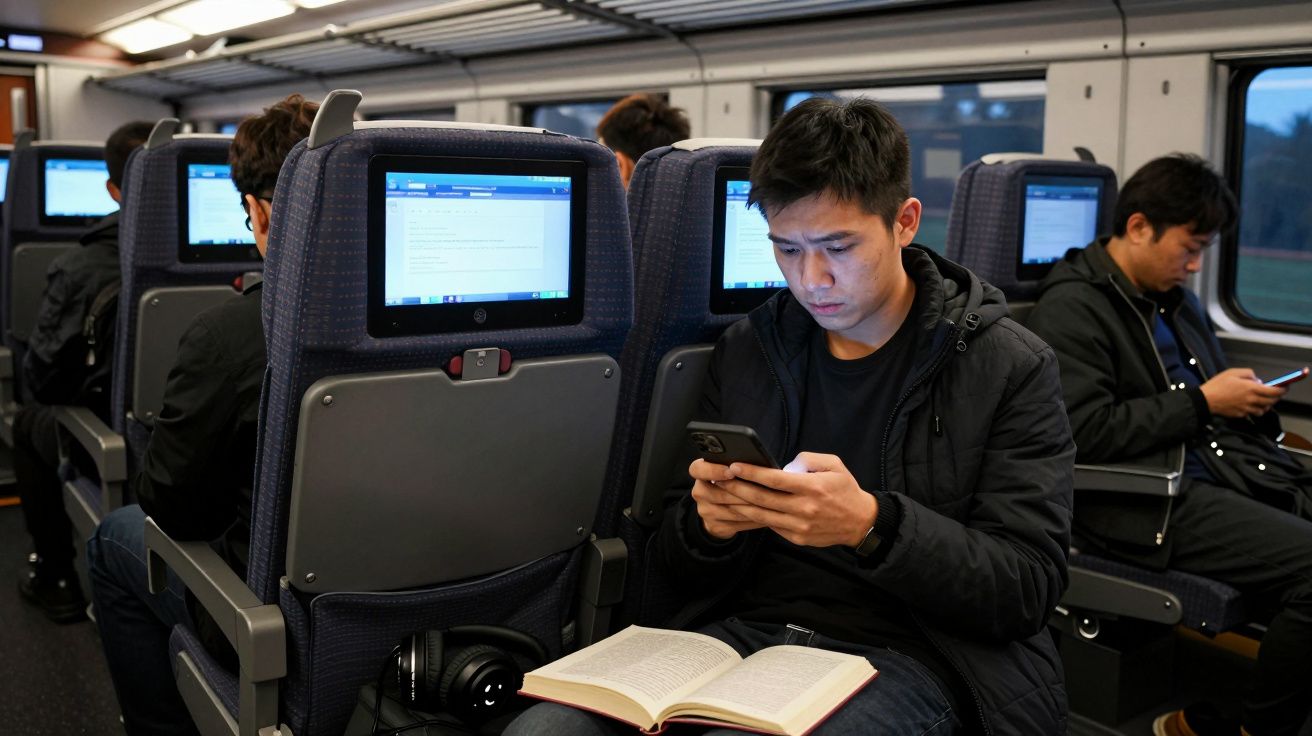

The carriage hums with the usual soundtrack: doors beeping, announcements crackling, a soft chorus of notification pings. Shoulders touch, eyes drop to screens. Before you’ve even reached the next stop, you’ve skimmed three “urgent” emails, mentally drafted two replies and started worrying about a meeting you’re not in yet.

By the time you walk into the office, you feel as if you’ve already worked half a day. Yet your timesheet still says 9am start.

Psychologists say that drained, slightly frayed feeling is not in your head. Turning your commute into a rolling inbox check-in quietly hijacks the part of the day your brain desperately needs for recovery, priming you to feel more exhausted than the journey itself ever could.

When the commute becomes your unpaid first shift

Once, the commute was mostly dead time: staring out of a train window, reading a book, getting mildly annoyed at delays and then moving on. Now it is often the unofficial opening act of the working day.

The boundary between “off” and “on” used to be physical. You left home, travelled, arrived at work. Email on phones, flexible hours and hybrid working have blurred that line so thoroughly that the working day begins the moment the 4G signal holds.

Psychologically, that matters. Researchers who study “boundary management” find that people need a clear sense of when they are working and when they are not. Your commute used to be a buffer - a neutral zone that helped your mind cross from one role to another. Fill it with emails, and you effectively delete that buffer.

What looks like “getting ahead” can quietly become “starting earlier, finishing later, and never really switching off”.

What constant checking does to your brain

Sitting on a train scrolling through emails feels passive. To your nervous system, it is anything but.

Every new subject line, red exclamation mark or ambiguous phrase acts as a micro-stressor. On their own, small. In a 45‑minute journey, relentless.

Psychologists point to several overlapping mechanisms:

Cognitive switching costs

Each time you open a different email, jump to your calendar, then back to your inbox, your brain has to refocus. That constant gear-changing uses more mental energy than staying with one task, even if each task is tiny.Attention without closure

On a commute, you often read messages you cannot properly act on: you see the problem but cannot fix it yet. That creates “attention residue” - part of your mind stays stuck on the unfinished issue, humming in the background.Anticipatory stress

An email about a performance review, a tricky client or a vague “can we talk later?” invites your brain to rehearse worst-case scenarios. Stress hormones rise in response to what might happen, not just what is happening now.Emotional contagion through text

Humans are wired to pick up on others’ moods. A sharp sentence from a manager or a panicked note from a colleague can colour your own emotional state for the rest of the journey.

Physically, you appear still: sitting, perhaps even lucky enough to have a seat. Neurologically, you are already at work, responding to demands, solving problems and managing social impressions - all before you have officially started.

Why it feels more tiring than the travel itself

Travel is tiring for simple reasons: standing, noise, crowding, delays. Yet many commuters notice a different quality of fatigue on the days they scroll their inbox from door to door.

Recovery science offers one explanation. Our brains need regular pockets of “psychological detachment” from work - minutes or hours where you do not think about tasks, colleagues or deadlines. Those pockets are when your stress systems recalibrate and your mental resources replenish.

Turn your commute into another work slot, and you lose one of the easiest, most automatic chances for detachment in your day.

That loss has knock-on effects:

- Your mental energy is already depleted when you arrive, so routine tasks feel heavier.

- You start the day with a sense of being behind, because you have spent the commute collecting problems rather than resolving them.

- You experience your job as more invasive, because work thoughts bleed into spaces that used to belong to you.

Over time, that pattern can turn “normal work tiredness” into something closer to chronic depletion. The journey itself has not changed; the mental load you place on top of it has.

The slot machine in your pocket

Not every email-checking commuter is frantically firefighting. Many are just… checking. A swipe here, a scroll there, almost on autopilot.

That, too, has a psychology.

Email works like a slot machine. Most messages are dull; a few are rewarding (praise, progress, good news); some are threatening (complaints, demands, criticism). That uneven mix keeps you coming back. Your brain gets a small hit of dopamine when you see something positive or resolve a tiny issue. It learns that checking “might” feel good.

On a commute, boredom and habit join in. The moment your mind wanders, your hand reaches for your phone. Before you notice, the entire journey has disappeared into low-level monitoring of things that could easily have waited.

Researchers describe this as “continuous partial attention”: your focus is never fully on the outside world, never fully on your inbox, always slightly braced for the next ping. Live like that for long enough, and your baseline state becomes lightly stressed and easily drained.

Not all pre-work email is bad - but it has to be deliberate

Psychologists are quick to say that context matters. For some people, a short, intentional email session before work can reduce anxiety, by preventing a nasty surprise at 9am or allowing them to plan their day with clearer information.

The key word is intentional.

- You decide when you will check (for example, the last 10 minutes of the train, not the whole ride).

- You decide what you will do (triage and flag, not reply to long threads on a cramped carriage).

- You decide what you will not touch (sensitive conversations or anything likely to stir you up when you cannot respond properly).

Without those boundaries, “just keeping an eye on things” tends to expand until it fills the entire commute, every day, regardless of need.

How to reclaim your commute without quitting your job

You do not need to delete your email app or move to the countryside to feel less wrung out by 9am. Psychologists suggest small, realistic adjustments that slowly shift the balance back in your favour.

1. Redesign the first and last 15 minutes

Treat the edges of your commute as protected zones.

- For the first 15 minutes: no work email. Listen to music, read, stare out of the window, or simply let your thoughts wander.

- For the last 15 minutes: if you choose to, do a focused check: scan for anything genuinely urgent, make a quick mental or written list, then put the phone away again.

That simple structure restores at least one short block of genuine detachment each way.

2. Turn off the loudest triggers

Full notification silence is not always realistic, especially in demanding roles. But you can tame the most draining alerts.

- Disable push notifications for newsletters, automated updates and low-priority lists.

- Keep only one or two channels marked as “urgent” - for example, a direct call or a specific app your team uses for true emergencies.

- Move your email icon off your home screen to reduce the pull of habit checking.

The aim is not to be unreachable; it is to stop treating every message as if it were critical.

3. Decide your “commute rules” and share them

Clear internal rules reduce guilt. Clear external rules manage expectations.

You might decide:

- “I do not reply to non-urgent emails on the train.”

- “I only read messages I can act on later without stewing about them now.”

- “If something is genuinely urgent before 9am, colleagues should phone or use X channel.”

If workload and culture allow, discuss these boundaries with your manager. Framing them in terms of sustained performance (“I’m fresher and sharper if my commute is not my first shift”) often lands better than “I don’t like checking email”.

4. Give your attention to something that actually restores you

The most powerful way to break a draining habit is to replace it with a better one.

On at least some journeys, experiment with:

- A book or podcast unrelated to work.

- A short mindfulness or breathing exercise with headphones.

- Looking out of the window and deliberately noticing details (weather, buildings, people).

- Writing a few lines in a notebook about anything except your job.

These alternatives are not self-indulgent extras; they are tools that help your brain downshift, so it has more to give when you really need it.

5. Watch how your energy changes

For a week or two, pay attention to how different patterns feel.

- On days when you constantly check emails on the commute, note your mood and concentration by mid-morning.

- On days when you limit or skip checking, compare.

Most people quickly see a difference. That evidence is more convincing than any generic advice, and it can help you argue for boundaries at work if you need to.

Common commute habits and what they do to you

| Habit on the commute | Likely effect on you | A gentler swap |

|---|---|---|

| Flicking through emails from door to door | High cognitive load, low recovery, feeling “on call” | One planned 10‑minute triage near the end of the journey |

| Reading tense threads you cannot answer yet | Anticipatory stress, rumination, mood dip | Flag for later and defer reading until you can respond |

| Responding to complex emails on your phone | Poor thinking, typos, frustration | Draft short notes or bullet points, send a proper reply at a desk |

| Keeping all notifications on | Constant micro-jolts of anxiety | Only allow alerts from true-urgent senders or channels |

FAQ:

- Is it really that harmful to check emails on the train?

It is not harmful in the sense of immediate damage, but doing it daily, unconsciously and for the full journey erodes the recovery time your brain relies on. Over weeks and months, that can significantly increase fatigue and make work feel more overwhelming.- What if my job genuinely requires me to be available before and after hours?

Availability is not the same as constant monitoring. You can stay reachable through one urgent channel (for example, phone calls) while still protecting yourself from the drain of reading every non-critical email the moment it arrives.- I get more anxious if I do not know what is in my inbox. Should I still cut back?

In that case, aim for deliberate, time-limited checks rather than total abstinence. A short, focused scan to see what is waiting - followed by a clear decision not to engage emotionally until you can act - often reduces anxiety without sacrificing recovery.- Does this apply to other apps, not just email?

Yes. Any work-related app that pulls your attention into tasks, conflicts or decisions during your commute can have a similar effect. Messaging platforms, project boards and calendar apps all deserve the same scrutiny.

Comments (0)

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!

Leave a Comment