The first time a fridge technician told me off, I’d just demonstrated how “satisfying” it was to slam my kitchen door shut and hear the jars rattle. He winced like I’d scraped cutlery on a plate.

“Do that every day for a few years,” he said, “and you’ll ring someone like me to ask why your food’s going off and your bills are up.”

It sounded dramatic. It also sounded like something a parent would say to get you to stop making noise. So I spoke to a handful of refrigeration engineers, pulled my own fridge away from the wall for a good look, and watched the smart meter while I “tested” the door the way I usually close it.

The verdict was unnerving: not instant disaster - just quiet, steady damage in exactly the place you never think about.

The thin rubber line that keeps the cold in and the warm out.

What actually happens when you slam the fridge door

On the surface, a slam looks simple: door, bang, closed. Inside the appliance, it’s a small storm.

Air has to move quickly when you shut the door. A gentle close lets it escape through tiny vents. A slam compresses it, hard, and the pressure wave hits the liner, the shelves, the hinges and the seal in one go. Bottles clack, eggs hop in their tray, screws and plastic joints take the shock.

Technicians described the same pattern again and again. Over time, repeated impacts:

- twist and crease the door seal (the rubber “gasket” that runs round the edge)

- loosen hinges so the door sags a few millimetres

- make the inner door panel flex and fatigue

None of this breaks on day one. It just gets a bit worse every month until one winter morning you notice the fridge running longer, or you find yoghurt at the back that’s not as cold as it should be.

One engineer showed me his least favourite party trick: slam the customer’s fridge door and watch it bounce back open a couple of millimetres. From the front it looks closed. From the side you can see a hairline gap all the way down.

“That gap,” he said, “is your electricity and your food safety leaking out together.”

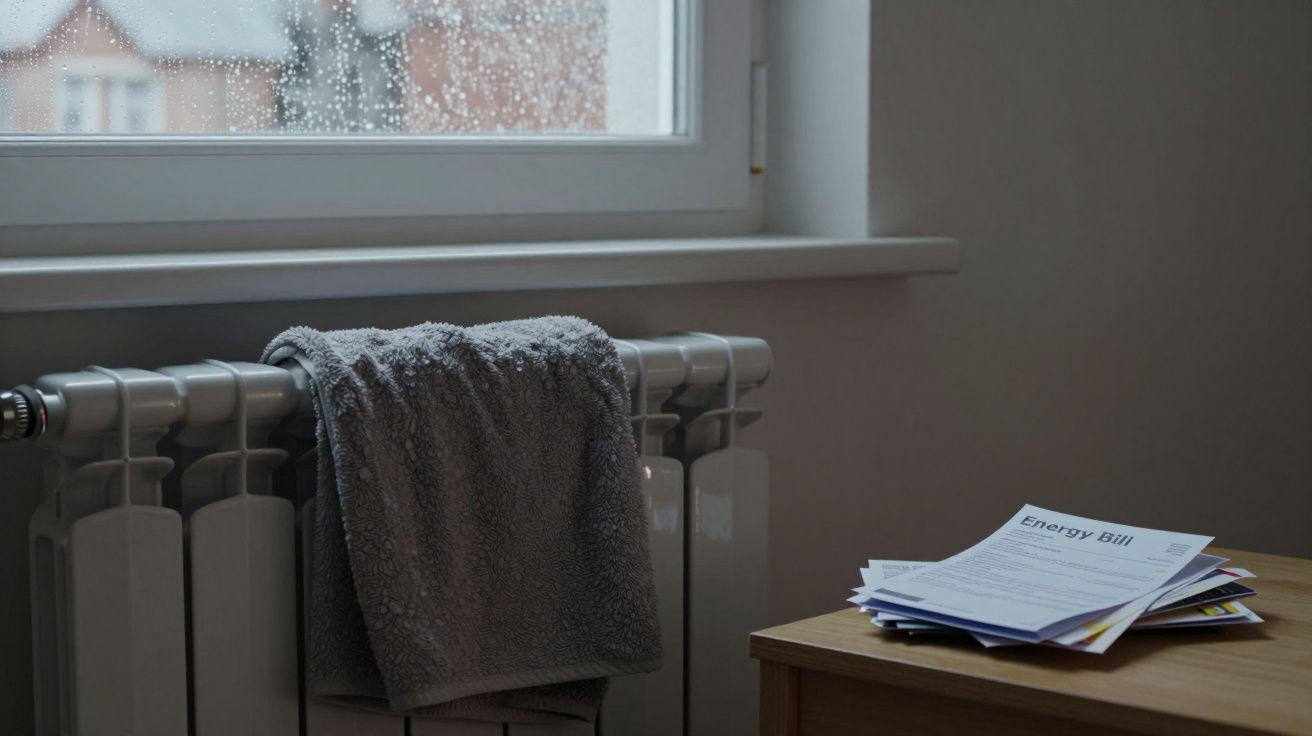

How a tired seal quietly empties your wallet

Fridges are basically insulated boxes with a small pump (the compressor) that moves heat from inside to outside. A good seal means the pump mostly has to deal with heat sneaking through the walls and from new food. A bad seal adds a permanent draught of warm kitchen air to the job.

Warm air in, cold air out, all day.

In energy terms:

- A modern, efficient fridge-freezer might use 150–250 kWh per year.

- Engineers I spoke to say a badly leaking door can add 30–50% to that.

- At around 28–30p per kWh in the UK, that’s roughly £15–£40 a year, per appliance - more if yours is older or lives in a warm kitchen.

The waste doesn’t shout on the bill as a line item. It hides inside the “background” number you’ve learned to ignore.

You also pay in other ways:

- The compressor runs hotter and wears faster, shortening the life of the appliance.

- The internal temperature swings more, which can shorten the life of food and increase the risk of bacteria growth.

- Freezers get heavy frost build-up around the door area, which insulates the wrong bits and makes them work even harder.

One technician described a flat where the freezer seal had split on the hinge side years earlier. The unit was using nearly double the expected electricity. The tenants only realised when the landlord finally approved a replacement and their direct debit dropped without them changing anything else.

The slow damage slamming really causes

Slamming is not the only way seals die, but it accelerates all the usual problems.

1. Creased and warped seals

Door gaskets are soft for a reason: they have to deform slightly to fill tiny gaps. That softness makes them vulnerable.

A hard slam:

- compresses the same spots over and over, so the rubber develops “set” and doesn’t spring back

- can twist the seal so it sits slightly rolled, creating a thin channel for air

- exaggerates any dirt or crumbs stuck on the frame into raised pressure points

Once a crease forms, every closure pushes that fold deeper. From the front the seal looks fine. Up close, you’ll see a section that no longer quite meets the cabinet.

2. Loose hinges and sagging doors

Fridge doors are heavy: glass shelves, large bottles, jars of things you meant to throw away in 2019. All of that hangs off a couple of hinges and a thin metal skin.

Add repeated slams and, over a few years:

- screws can back off a fraction

- plastic hinge mounts can crack

- the door can drop just enough that the top corner no longer seals tightly

Technicians often spot this because a sheet of paper pulls out easily at the top hinge side, but is gripped tightly near the bottom.

3. Cracks in liners and insulation bridges

In more severe cases, the inner plastic liner flexes so much it eventually cracks around the door opening. That exposes insulation foam, which can absorb moisture and conduct heat.

It’s less common than a tired seal, but when it happens, there’s not much to repair. You’re into “live with the waste” or “replace the appliance” territory.

A 5‑minute DIY seal check technicians wish everyone did

You don’t need special tools to see if slamming (or time) has already taken a toll. You just need five minutes and a bit of paper.

The paper test

- Take a strip of ordinary A4 paper.

- Close the door on it so half is inside, half outside.

- Gently pull. You should feel firm resistance all the way round the frame.

- Move the paper every 5–10 cm. Any spot where it slides out easily is a suspect area.

- Take a strip of ordinary A4 paper.

The torch test (at night)

- Put a bright torch inside, pointing towards the seal.

- Turn off the kitchen lights.

- Look all around the door edges. If you can see light leaking, air is leaking too.

- Put a bright torch inside, pointing towards the seal.

Look, touch, listen

- Look for mould, crumbs or cracks in the gasket, especially at the corners.

- Touch the seal: it should feel flexible and slightly rubbery, not brittle.

- Listen to the compressor. If it seems to run almost constantly when the door is shut and the room isn’t hot, that’s a clue.

- Look for mould, crumbs or cracks in the gasket, especially at the corners.

Technicians often run a similar set of checks before they get their gauges and meters out. If your fridge fails the paper or torch test, slamming is no longer just a bad habit - it’s money out of your account every day.

Everyday habits that quietly wreck fridge doors

Slamming is the headline villain, but it’s rarely alone. The engineers I spoke to had a shortlist of “door killers” they see again and again:

- Letting the door swing and hit the frame at speed instead of guiding it closed.

- Packing the door with heavy items (multiple four-pint milk bottles, full wine racks) so the hinges are under constant strain.

- Yanking the door open immediately after closing it, fighting the suction instead of waiting a few seconds.

- Using the door as a leaning post while you look for snacks.

- Never cleaning the seal, so grit and sticky spills act like sandpaper and glue.

You don’t need to live like a museum guard. You just need to switch from “impact” to “contact”.

Engineers’ preferred script is simple:

- Close the door by the handle or edge, not by pushing the top or the glass shelves.

- Aim for a firm, decisive close, not a shove from across the room.

- If the door seems “stuck” because you’ve just opened it, wait five seconds. The pressure equalises and it will open easily without a wrench.

- Don’t overload the door. One large bottle per shelf is plenty; use interior shelves for the rest.

How much money a new seal can actually save

If your tests show obvious leaks, you almost always have three options:

Clean and gently reshape

Warm soapy water and a soft cloth can remove grime that’s preventing a good seal. For minor kinks, running a hairdryer on low over the area (carefully, not too close) while gently massaging the rubber can sometimes help it relax back into shape.Replace the gasket

- Many modern fridges have clip-in or screw-in seals you can buy as spare parts.

- Parts typically cost £25–£60; a professional call-out and fit might run £80–£150 depending on where you live.

- If your seal is torn, rock-hard, or mouldy beyond cleaning, replacement is the only sensible option.

- Many modern fridges have clip-in or screw-in seals you can buy as spare parts.

Replace the appliance

On very old, inefficient units, a failing seal is often the nudge to retire it. A modern A‑rated fridge-freezer can use less than half the energy of a 15‑year‑old one even when both are in perfect condition.

A technician walked me through a real example: a mid-sized fridge-freezer measured around 120 kWh/year when new. Several years - and a cracked seal - later, it was drawing closer to 200 kWh/year. A new gasket and proper door alignment brought it back to roughly 130 kWh/year. At 30p per kWh, that’s about £21 saved every year, on top of better food safety.

The payback timescale isn’t fireworks. It’s more like tightening a dripping tap. But it’s there, and it keeps going quietly once the work is done.

Simple rules to keep your fridge door healthy

Think of your fridge door like a car door you actually paid for yourself. You wouldn’t slam it every time you got in.

A quick routine most technicians would sign off on:

- Close, don’t slam. Aim for a single, smooth push until you feel and hear the seal engage.

- Teach kids the “click, not crash” rule. Make a game of who can close it most quietly.

- Keep heavy bottles on interior shelves where possible.

- Wipe seals clean every few weeks with warm, mild soapy water, then dry thoroughly.

- Do the paper test twice a year, or if you notice more condensation or longer run times.

Tiny habits, repeated, either destroy the seal or protect it. The effort is the same; the direction is different.

| Key point | Detail | Why it matters |

|---|---|---|

| Slamming twists seals | Repeated impacts crease and misalign the gasket over time | Small gaps add up to big heat leaks and higher bills |

| Leaks cost real money | A tired seal can add 30–50% to a fridge’s energy use | You can be paying £15–£40 a year extra per appliance |

| Checks are easy | Paper strip, torch, look–touch–listen in 5 minutes | Lets you fix issues before they kill the fridge |

FAQ:

- Is an occasional hard close really that bad for my fridge? One slam won’t kill it. The problem is the habit - daily or hourly impacts over years that gradually distort seals and loosen hinges.

- How can I tell if my slamming has already damaged the seal? Use the paper and torch tests, and inspect the gasket for flat spots, cracks, or areas where the door doesn’t sit flush, especially near the top corners.

- Can I fix a bad seal myself, or do I need a technician? Many clip-in seals are DIY‑friendly if you’re patient and follow the manual. If the door needs re‑aligning or the hinges are worn, calling a professional is safer.

- Is it cheaper just to accept the extra electricity than to replace the seal? In the short term you might spend more on the repair than you save in a single year, but over the typical life of a fridge the energy and reduced food waste usually repay the cost.

- Does this apply to freezers as well as fridges? Yes. Freezer seals are just as vulnerable, and leaks often show as heavy frost build-up around the door area and a motor that seems to run almost constantly.

Comments (0)

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!

Leave a Comment